Last week, the top news item was that a magistrate had issued warrants for the arrest of eight Hong Kong residents, now living abroad, for alleged offences under the national security law. The government also promised HK$1 million rewards for information leading to each of their arrests and prosecutions.

Soon after the announcement, Ronny Tong, a lawyer and member of the Executive Council, a government advisory body, had something to say about the mechanics of getting the wanted persons back to Hong Kong.

He acknowledged that securing the extradition of the eight Hong Kong residents from their homes in Canada, Australia, the US, and the UK was impossible. Extradition arrangements between those countries and the city had been suspended. However, he said, if any of the eight were rash enough to travel abroad, a friendly country might rearrange their itinerary so that they ended up in Hong Kong.

When a person is returned to the place where he is wanted on suspicion of committing a criminal offence under an extradition arrangement, the process is sometimes called “rendition.” Where no extradition arrangements exist or are ignored, the process is called “extraordinary rendition,” a polite way of describing forcible abduction at the behest of a state.

Tong’s remarks made me think of a minor English statesman, Sir George Downing, and his contribution to extraordinary rendition nearly 400 years ago.

Downing – the knighthood was still years in the future – had been on the winning side in the English Civil War, which ended with the 1649 execution of the king, Charles I. However, the experiment in a quasi-republican dictatorship that followed under Oliver Cromwell and his son, Richard, was unsuccessful, and the monarchy was restored in 1660.

Downing was one of the many former supporters of Oliver Cromwell who found it convenient to forget his former allegiance and swear loyalty to the executed king’s son, Charles II. Like many political converts, Downing would be more royalist than the king.

In 1661 Downing was appointed ambassador to the Dutch Court at the Hague. He had previously served Oliver Cromwell in that post and had established a network of spies and agents to hunt down the royalists who had fled England to Europe after the death of Charles I. He refreshed the web and set its spiders to hunt down his former colleagues who were now seeking refuge in the Netherlands and other places on the continent because they had signed the death warrant of Charles I.

In early 1662 he managed to lure three of them, including his old friend and regimental commander, to the city of Delft. By a combination of bribes, cajolery and deceit, he persuaded the local officials that their arrests had been authorised by a state official, which was true, and that he, Downing, had the authority to arrest and detain them on behalf of the state official, which was untrue.

Before anyone could check with officials in the Hague or enquire what was planned for the three men, Downing had arrested them and bundled them onto a ship bound for England. The trio were executed particularly brutally (half-hanging, castration and disembowelment, all when still conscious) a few weeks later.

For this and other services to the crown, Charles II knighted Downing in 1663. In 1682, the king granted him a lease on a plot of land adjacent to St James Park and the right to build a few townhouses. The row of houses he built was named after him, so the address of the British prime minister’s official residence will always be connected to the phenomenon of extraordinary rendition.

It is impossible to guard against attempts at extraordinary rendition if a state is determined to get its man or woman.

In 1984, a former Nigerian government minister, Umaru Dikko, was living in London. The Nigerian government accused Dikko of embezzling over £600 million. It wanted him back in Nigeria but did not request extradition.

With the help of a former Israeli intelligence officer, a team kidnapped Dikko from his London home. They then drugged him, placed him in a crate, and drove to Stansted airport to a waiting Nigerian Airways 707 and a nervous young Nigerian diplomat who sought to clear the container as diplomatic baggage.

An astute customs officer thought the hurried arrangements were unusual and then heard on the news that Dikko had been kidnapped. The officer insisted that the crate be opened. Following diplomatic protocols, the customs officer ensured Foreign Office officials were called to oversee the crate’s opening. The customs officer opened the crate to discover the drugged Dikko and a fully conscious doctor whose job was to monitor him to ensure he stayed alive on his journey to Nigeria.

Although Nigerian officials protested that Dikko was a thief who needed to face justice, the British authorities were not impressed. Four people involved in the kidnapping who could not claim diplomatic immunity received prison sentences. Diplomatic relations between the UK and Nigeria broke down. They were not restored for two years.

Dikko’s unpleasant experience was not the first attempt at extraordinary rendition in London.

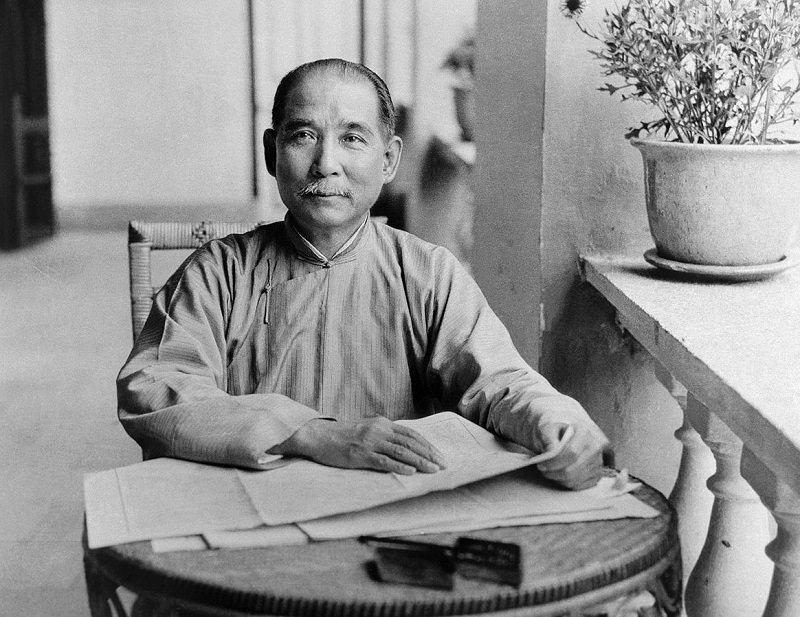

In 1896, Sun Yat-sen was living in the UK capital, raising money for the Revive China Society to instigate a revolution in China. Members of the Chinese Legation kidnapped Sun and detained him in the Legation premises for 12 days until the British government intervened. Legation staff had planned to return Sun to China for trial.

The Foreign Office told the Chinese side that Sun’s detention abused diplomatic privilege, and Sun was released.

On 15 February, 1897, the Foreign Office Under-Secretary, George Curzon, stated the following in parliament about the incident in response to a question:

“As trustworthy evidence was received a note was addressed by Lord Salisbury to the Chinese Minister pointing out that Sun Yat Sen’s detention was an abuse of the diplomatic privilege enjoyed by the Chinese Legation, and requesting his immediate release. This request was complied with on the 23 October… Sun’s detention was certainly not warranted by International Law, and was regarded as a serious abuse of the privileges and immunities which are granted to foreign representatives, and the Chinese Government were so informed through Her Majesty’s Minister at Peking and requested to give strict instructions to their Minister in London to abstain carefully for the future from any acts of the kind.”

A state may, however, succeed in pulling off an extraordinary rendition and returning a person to the place where they are wanted, but the story does not end there. If the person rendered is wanted for a criminal offence, there has to be a trial. Courts are meant to be independent of the prosecution. What, then, do courts make of kidnappings and forced repatriation?

Courts are very pragmatic. If irregular methods have obtained evidence, it does not mean that a court will not act on it and convict a defendant who might have a legitimate complaint about rule-breaking police officers. This pragmatism has extended to overlook how a defendant has been brought to court. For a long time, English and American courts have refused to inquire thoroughly into how the prosecution brought a defendant to court. All that mattered, they reasoned, was that the defendant would have a fair trial.

However, in 1993, the House of Lords in the UK refused to hold a handkerchief to its nose any longer when it had to deal with the extraordinary rendition to the UK of Paul Bennett.

Bennett was a New Zealand national who had allegedly bought a helicopter in the UK by deception and then taken it to South Africa. The English police knew that Bennett was in that country, but there was no extradition treaty between the UK and South Africa.

The English police asked their South African counterparts to do them a favour and put Bennett on a plane bound for London, which they did after a ruse in which Bennett was ostensibly deported to New Zealand via Taipei. However, after Bennett landed in Taipei, two South African police officers intercepted him and arranged for him to be flown to London via South Africa, where he was arrested and taken to court.

Four out of the five law lords who heard the case held that it would offend the court’s conscience if they permitted Bennett to be tried, even though there was no question of him being legally represented and able to enjoy a fair trial.

In his judgment, Lord Bridge wrote

“There is, I think, no principle more basic to any proper system of law than the maintenance of the rule of law itself. When it is shown that the law enforcement agency responsible for bringing a prosecution has only been enabled to do so by participating in violations of international law and of the laws of another state in order to secure the presence of the accused within the territorial jurisdiction of the court, I think that respect for the rule of law demands that the court take cognisance of that circumstance. To hold that the court may turn a blind eye to executive lawlessness beyond the frontiers of its own jurisdiction is, to my mind, an insular and unacceptable view.”

The House of Lords judgment was that the abduction and forcible return to the U.K. was so shocking that trying Bennett would be an abuse of the court.

Should one of the eight’ “street rats” – as these people who have not been convicted of an offence and should still enjoy the presumption of innocence were referred to by the chief executive – be returned to Hong Kong in this unconventional manner, it will be for the Court of Final Appeal, because there will be appeals to that court, to decide whether the rule of law as described by Lord Bridge 40 years ago holds good in Hong Kong in the age of the national security law.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.