After hundreds of thousands of people marched on June 9, the Hong Kong government decided to go ahead with its extradition law plans despite widespread opposition.

Three days later, the Legislative Council was supposed to debate the ill-fated bill. But it never happened, as protesters surrounded the legislature, forcing the meeting to end prematurely. That day, protesters clashed with the police; some threw bottles and metal bars at officers, and police responded with tear gas, rubber bullets and sponge grenades.

Stephen Lo, then-police commissioner, quickly declared that protesters had participated in a “riot.” His remarks sparked a new demand for the protest movement: for the authorities to stop characterising the protest as a riot, and demonstrators as “rioters.”

‘Vague and arbitrary’

The term “riot” was significant because of the charge behind it. Under section 20 of the Public Order Ordinance, when anyone takes part in an unlawful assembly and commits a breach of the peace, then it is considered a “riot.” All those present are rioters. And rioting carries up to ten years in jail.

But the colonial-era charge has long been criticised since the requirement of “breach of the peace” is vague.

Lo Kin-man was present during the unrest in Mong Kok in February 2016. He threw a water bottle and sand at police officers and was sentenced to seven years in jail, the most serious punishment yet in cases relating to the 2016 clashes.

The maximum sentence under section 20 of the Public Order Ordinance is even higher. Those convicted face 14 years behind bars if they take part in a riot and unlawfully damage any motor vehicle, tramcar, aircraft, vessel, building, railway, machinery or structure.

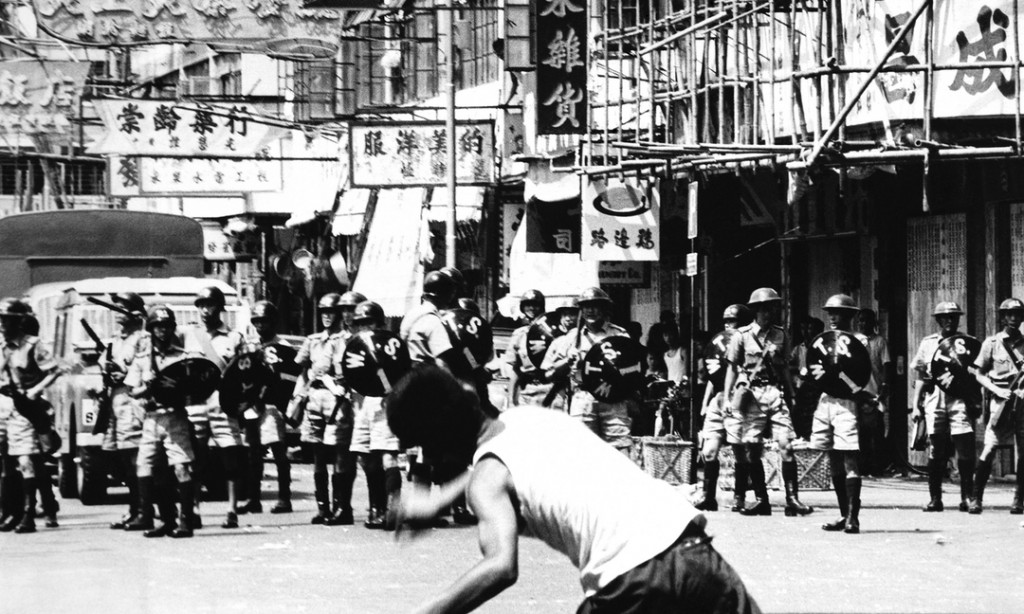

The charges were only added to Hong Kong law in 1970 following the 1967 leftist riots. During which, 8,074 suspected bombs were planted – 1,167 contained real explosives. At least 51 people died during the riots, including ten police officers. Over 802 people were injured.

Activist Edward Leung was cleared of a rioting charge over the 2016 unrest in March 2019, but was convicted on a separate rioting charge and sentenced to six years in jail. The case prompted 11 international parliamentarians to urge reforms to the Public Order Ordinance.

They said the Ordinance was “an outdated colonial-era law which has been repeatedly criticised by the United Nations Human Rights Committee for violating international human rights standards,” and the definition of rioting was vague and arbitrary.

“These convictions [over rioting] are designed by the government to intimidate protesters, and they are having the desired chilling effect: young people are increasingly demoralised at the lack of justice,” they said.

Pro-democracy lawmakers have drafted a bill to amend the Public Order Ordinance to change the definition of riot, and to reduce the maximum sentence to three years. But it depends on the government as to whether to accept the bill, as it cannot be tabled in the Legislative Council without government consent.

Hundreds charged

The anti-extradition bill protests, which began this June, are still ongoing after six months. But protesters are making wider demands including an independent commission of inquiry to investigate police behaviour, the unconditional release of all arrested protesters, and universal suffrage, as well as retraction of the riot characterisation.

As of December 16, the Hong Kong police said that 6,105 protesters had been arrested over the demonstrations, of whom 978 have been prosecuted. So far, 517 of them have been charged with rioting.

One of the reasons for the high number of protesters facing the charge is due to the siege of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. The government stated that anyone inside the university would be charged with rioting.

Those arrested included 51 people who said they were volunteer medics or journalists. Darren Mann, a Hong Kong-based surgeon condemned the police for arresting medics, saying that the move violated international humanitarian standards. He published his criticism in the leading medical journal Lancet.

There were also people who protested outside the school or in nearby areas in an effort to rescue those inside. Nevertheless, 242 of them were arrested and charged with rioting. Court proceedings for the 242 continued until 1am at some of the city’s courts.

Controversial cases

There have also been some controversial prosecutions under the rioting charge.

Elaine To, Henry Tong and Natalie Lee were all arrested near Des Voeux Road West in Sheung Wan on July 28. Defence lawyers previously told the court that To and Tong were trying to help Lee to her feet when the trio were arrested by riot police.

Prosecutors have also been criticised for withholding evidence from defence lawyers in cases involving 16 people charged with rioting. The defendants included frontline social worker Jackie Chen who was arrested on August 31 in the vicinity of Wan Chai and Causeway Bay. Chen has often been seen on the frontlines urging the police to de-escalate and not use force.

Raymond Yeung, a liberal studies teacher at the elite Diocesan Girls’ School, was arrested on June 12 in Admiralty on suspicion of rioting and was released unconditionally later in October.

But he was hit in the face by a police projectile and fragments of his shattered glasses went into his eyes. His right eye has only 2.5 per cent eyesight remaining, according to a Ming Pao interview.

The term “rioter” has appeared over 200 times in government press releases and countless times in state media reports during the protests. But demonstrators remain critical of the term, with a banner unfurled by activists in the legislature chamber on July 1 reading: “There are no rioters, only a tyrannical regime.”

Hong Kong Free Press relies on direct reader support. Help safeguard independent journalism and press freedom as we invest more in freelancers, overtime, safety gear & insurance during this summer’s protests. 10 ways to support us.