Some time back in around 2015, five researchers from, respectively, Harvard, the London School of Economics, the University of New South Wales (disclosure: my alma mater), the University of Chicago and Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich got together. They were interested in the dynamics of political protest movements and directed their attention to Hong Kong.

They had – or declared themselves to have – no relevant or material financial interests – i.e., they were not climate researchers being paid by ExxonMobil, tobacco researchers being paid by Philip Morris or insurgents being paid by the CIA (or its fronts).

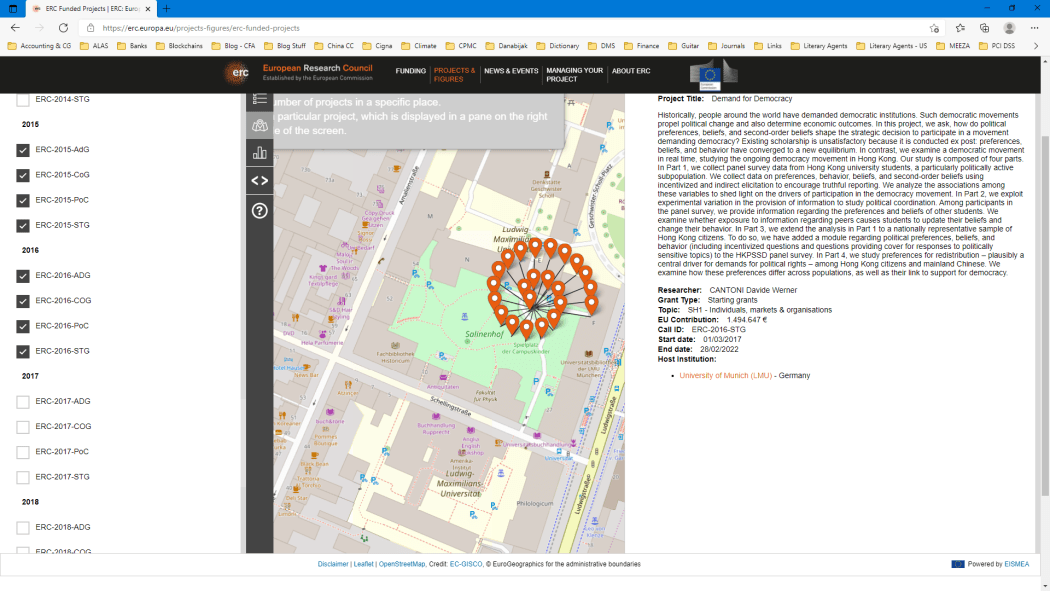

They applied for and were awarded a grant from the European Research Council under its Horizon 2020 programme. This grant, number 716837, was for the research programme Demand for Democracy, with a total funding of €1,494,647 (HK$14 million) during its continuance from 2017-2022.

Parts 1 and 2 of the programme focused on the student population. Part 3 extends the programme to study the population of Hong Kong as a whole, and Part 4 to include residents of the People’s Republic of China. Given those numbers, it seems likely that the amount allocated to Parts 1 and 2 was relatively small.

As is the norm in social science research, some smoke and mirrors was necessary. Students were told that volunteers were needed to count crowd sizes, at both the July 1, 2017 protest march and, a week later, at the MTR. The response rates were not significantly different. The students duly collected took the photos as instructed and were paid. They were also asked, through presumably devious means, if they would have attended the march anyway; about 40 had not planned to but did.

Mindful of the students’ safety, the researchers assessed that, given that every single July 1 March from 2003 to 2016 had been entirely peaceful, the risk was no larger “than those ordinarily encountered in daily life of the population.” The march was legal; people were exercising their right under Article 4 of the Basic Law to assemble freely and received a Letter Of No Objection from the police. Indeed, the government said in a statement that it respected the right to peaceful assembly.

The following year, in the 2018 march – also legal and LONO’ed – the researchers followed up. They did not pay, encourage or discourage anyone to attend, but instead looked at those in their sample to see who had attended both marches. The researchers’ conclusion was, in plain language, that money may induce a person to attend a rally once, but that his or her peers are a far greater influence on whether the person will go back a second time.

The results of the first two parts are in the snappily entitled paper, Persistent Political Engagement: Social Interactions and the Dynamics of Protest Movements, published in the just-released June edition of the American Economic Review: Insights.

An editorial in Sing Pao newspaper declared that the smoking gun had been found. Subsequent pieces in various pro-Beijing papers said the research paper proved without doubt that foreign forces had paid students to protest (the students were paid to count crowd sizes, not to protest) at the 2019 (not 2017) march. The 2019 march did turn violent, albeit only at the fringes and unlike the 2017 march.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that the research took place after the 2014 pro-democracy Occupy movement, which was perhaps a factor in Hong Kong being chosen for it. It is also worth pointing out that the researchers are clever people at some of the world’s top universities. As such, it is not merely credible but likely that in 2015 they anticipated that, in 2018, someone would murder his girlfriend in Taiwan, that Hong Kong’s CENO would be morally outraged, rush through an unpopular bill and thereby spark an uprising that would ultimately land us where we are.

Quite.

The thing about conspiracy theories is that any inconvenient fact is brushed aside with the stock response: “Well, they would say that, wouldn’t they?” The five researchers’ declarations of financial motivation are whitewash for the naive: at best, the researchers were manipulated by malevolent forces, at worst, far from being innocent academics, they are part of a cabal scheming to achieve the overthrow of China’s government.

Nor is the European Research Council the arms-length funder of research it purports to be, but a front for the EU’s well-known spy apparatus. To suppose that the EU has no such apparatus is, again, naive – of course they would want you to think that. The fact that the paper was published now, two years after the research, is nothing to do with “so-called” peer-review, but was to ensure that it was vetted to disguise the fact that the EU was interfering in Hong Kong’s affairs.

As to the protest, let’s set aside the researchers’ claims that only a few hundred students (849, to be precise) were involved in the research, that no more than 40 extra, or 0.1 per cent, attended the march (most were going to go, anyway), and that only half of them were paid. Had the research not taken place, the theorists crow, almost none of the 50,000-odd marchers would have turned up. They turned up, not because they were protesting, but in anticipation that they would be paid (to count each other). And paid by the European Research Council, no less. Money laundering, cut and dried!

As to the payment, the researchers’ claim in the following is nothing more than a wolf in sheep’s clothing: “Directly paying for turnout could potentially generate a set of compliers [those students who are in the study] very different from the typical protest participants we hope to study. To generate a strong first stage [the 2017 rally] without paying directly for turnout, we pay for behaviour conditional on turnout: providing information that would help estimate crowd sizes at the protest.”

The fact that, the following weekend, another group was paid to estimate crowd sizes in MTR stations was, of course, just more camouflage. (For the pecuniary-minded, the payment was HK$350.)

For years, the Hong Kong government has been attempting to blame foreign interference for its political unrest. In November 2019, a certain other journalist got very excited about the US’s National Endowment for Democracy, which turned out to be a squib so damp it was soaking. This latest bout of hysteria portrays an even more ludicrously distorted version of reality.

It is plausible that individuals who live overseas have sought to get people out on to Hong Kong’s streets. It is plausible that some of those individuals paid into crowd-funding platforms in the full knowledge that their money would be used to break the law, and sometimes even for violence. It is even plausible that some of those people seek to overthrow the Communist Party of China.

But that is not the narrative that is being bandied around. The narrative being bandied around is that foreign governments are motivating, directing and funding the protests; that some protesters are merely naive but that others – that “tiny minority” – are agents of those foreign governments; that the entire dissatisfaction and, later, insurgency, was not home-grown but implanted.

That’s a big claim to make. I am not saying it is utterly implausible, but five boffins in ivory towers does not, for me, cut it. Mind you, at the current exchange rates, the grant money works out as about 43,000 payments of HK$350 – the size of the 2017 and 2018 marches. Q.E.D., I suppose.

Correction 6.15: A previous version of this article mistakenly stated that a government statement was taken down from its website. The correct link has been included.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.